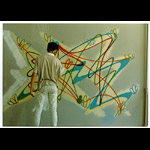

“Rip ”, “Scene ” and “Risk-E ”

Hip Hop Graffiti Spray Can Art

June - July 1988

An early exhibition of graffiti at the grunt gallery, Hip Hop Graffiti Spray Can Art was controversial for bringing this art form into the gallery from the street. Three young artists covered the gallery walls with gestural “spray can ” painting including “tags ” that fused image and text into graphical, symbolic signatures.

STYLES BEYOND COMPARE

HIP HOP GRAFFITI ART

by "Rip", ''Scene'' and ''Risk-E''

Download as pdf, 86K

Requires the free Adobe Reader

Hip hop graffiti art, or hip hop spray can art, as it is more recently referred to, developed in New York City's inner cities in the mid 1970s. What began as part of a youth subculture called hip hop and included breakdancing, rap music and subway graffiti, hip hop spray can art has moved out of the subways and spread around the world as a youth street art movement.

Originally a highly competitive form of male identity and status expression, simple name 'tags' became more and more elaborate in the pursuit of a writing style that could outdo all others. The writer's name was abstracted using certain formats of letters, such as bubble style or 3-D letters, and eventually became indecipherable except to the initiated. The use of a variety of nozzle tips, including those from oven cleaner aerosol cans, provided more technical freedom.

Embellishment of background urban landscapes of graphic designs, clouds, arrows and stars were added. More use of bright colours and modifying letters with effects like cracking, exploded or dripping all contributed to the desired effect of power and movement. Messages, sometimes personal, sometimes social or political, began appearing alongside the writer's tag. Alter ego characters, inspired by TV and comic book superheroes, were imbedded in the mural designs. Writers began working together in collaborative efforts on highly complex works. Aesthetic canons and a complex social system developed, including an in-group language used to evaluate their work. 'Kings', not 'toys', were masters because they could 'get up' with 'burners' and were good enough not to have to 'bite' other writers' styles or 'go over' their rivals' work.

Around 1984, through mass media exposure and travelling exhibits by the NYC writers, this form of aggressive youth expression began emerging in other urban centres from Amsterdam to London and Sydney with national and regional styles developing. Enter 'Rip', 'Scene' and 'Risk-E' in Vancouver. Inspired by movies such as Breakin' and Beat Street, these young men were among a handful who began the process of self-training, first practicing on paper with felt pen designs illustrated in a book on NYC graffiti. Subway Art was both how-to manual and bible to them. Eventually they felt confident enough to take their tags to the streets and soon began executing full-scale spray paint murals or 'pieces'.

Not only have they adopted the formal aspects of the art, but, to some extent, adhered to the hip hop way of life – language, dress code and listening to rap music are all accepted as components of this art movement. But, removed from its original context, much of its meaning gets lost or is diffused. Especially in Vancouver, where only a handful of young men participate, it is impossible to capture the competitive energy that provides the principal motivation for continuing to develop new lettering styles. Nonetheless, the work of 'Rip', 'Scene' and 'Risk-E' has evolved over the last three years so that each has a recognizable approach. 'Rip', originally from San Francisco, began as a break-dancer. Now, however, he is recognized by his peers in Vancouver as the most innovative writer, refusing to use a style once it has become 'stale' – i.e. been used by others. He claims he can "invent a new style every day." 'Scene' works meticulously with a free, loose hand and has stretched the limits of the prescribed formats in developing a highly abstract, wild style. He has recently begun using geometric design templates to produce a hard edge to contrast the soft mist-like fading technique. 'Risk-E' has perfected the technical execution while remaining compositionally conservative. He works at high speed, executing fine, smoothly flowing lines and has devised a method of virtually eliminating paint drips – the dread of most writers.

Although, to a great extent, these artists work in the dead of night, risking arrest, they do not see themselves as destructive vandals, but as artists using public space to express themselves and beautify their city. As 'Risk-E' put it in a recent interview, "If this is a crime, then it's a beautiful crime." Of course, there are always concerns being expressed about the rights of any individual to appropriate public space, imposing unsolicited images on the public. As part of an effort to remove themselves from the controversy surrounding the illegality of graffiti writing, 'Rip', 'Scene' and 'Risk-E' have participated in a number of commissioned art projects including the Mexican Pavilion at Expo '86, commercial storefronts, skateboard bowls, school murals and an exhibit at the UBC Museum of Anthropology. And, like their counterparts in NYC, the three Vancouver writers are transferring their designs onto jean jackets and T-shirts in a commercial enterprise.

The grunt project is part of an effort by the artists to extend their form of expression into the legitimate art community. By applying their spray paint to the inside of the gallery's walls they are challenging the public to recognize their work as art, not merely "mindless vandalism." The transition from street to gallery walls is part of the hip hop tradition and has been successfully attempted by writers elsewhere; indeed it becomes easily incorporated into the status-seeking system which is so important in the subculture. Even so, the extent to which this "taming" experiment will affect it is a concern expressed by all three writers who agree that hip hop, no matter how it may grow and develop as a legitimate art form and wherever else it may be found, ultimately belongs on the streets.